April is Sexual Assault Awareness Month — Learn about the compelling history of Denim Day, how sexual violence manifests in the context of abusive relationships, and how Sanctuary staff are taking action.

April is Sexual Assault Awareness Month— a crucial time to rally together, educate ourselves about the harsh reality of sexual violence, and support survivors on their journey to healing. One of the most notable initiatives during this month is Denim Day, a global movement that transforms ordinary denim jeans into a powerful symbol of protest against sexual violence.

In this blog post, we’ll take a deep dive into the compelling history of Denim Day, explore how sexual violence manifests in the context of abusive relationships, and share our staff’s unforgettable experience participating in the NYC Denim Day March and Rally.

What is Denim Day?

Denim Day was born out of a desire to challenge and change a deeply flawed narrative surrounding sexual violence.

In 1998, the Italian Supreme Court made a shocking decision to overturn a rape conviction. The justices argued that the victim’s tight jeans suggested she must have helped her attacker remove them, which they wrongly equated to consent. This outrageous ruling sent shockwaves through Italy and beyond, as it reinforced the damaging myth that clothing can determine responsibility for sexual assault.

Fired up and ready to fight back, women in the Italian Parliament staged a bold protest the very next day. They wore jeans to work in a defiant stand against the court’s decision and the misconceptions it perpetuated. This courageous act of solidarity soon blossomed into an international movement, with Denim Day now observed worldwide every April as part of Sexual Assault Awareness Month.

Sexual Violence Within Abusive Relationships

Sexual violence in the context of abusive relationships is a complex and often overlooked issue. Abusers often employ sexual violence as a weapon to exert power and control over their partners, using it to manipulate, degrade, and humiliate. It can take many forms, including rape, unwanted sexual contact, and sexual coercion.

Abusive relationships are characterized by a pattern of behaviors that are used to maintain power and control over the victim. This can include physical, emotional, and sexual abuse. Sexual violence is just one part of this pattern of abuse, but it can have lasting and devastating effects on the victim’s physical and emotional well-being.

Sexual violence in abusive relationships is often not recognized or reported, in part because of the shame and stigma that surrounds it. Victims may feel trapped, isolated, and powerless to leave the relationship, particularly if they are financially dependent on the abuser or have children together.

Understanding the complex ways sexual violence presents in the context of abusive relationships is crucial to supporting survivors and dismantling the systems that perpetuate abuse. By recognizing these intricate dynamics, we can better advocate for survivors and work toward effective prevention strategies.

Watch our webinar to learn more:

At Sanctuary, We #WearDenim

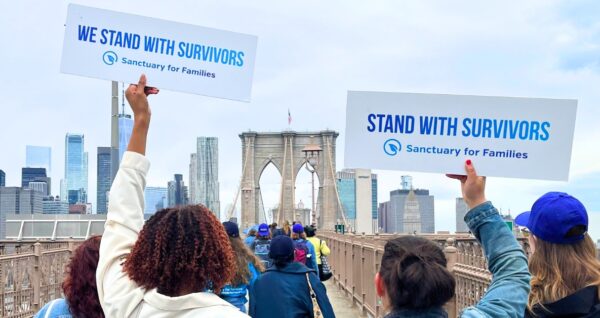

On April 24, 2023, Sanctuary staff members united for a cause dear to our hearts—the NYC Denim Day March and Rally. We proudly wore our denim as we marched across the Brooklyn Bridge from Brooklyn Borough Hall to Foley Square, joining forces with fellow advocates, survivors, and supporters. Together, we raised our voices against sexual violence and domestic abuse, championing a culture of consent, respect, and safety for all.

You Are Not Alone: Resources and Services for Survivors

At Sanctuary for Families, we’re committed to standing with survivors every step of the way. Our comprehensive services include clinical, legal, shelter, and economic empowerment support, all tailored to meet each individual’s unique needs.

If you or someone you know is experiencing domestic or sexual violence in New York, please reach out to our hotline at 212-349-6009 or visit our Get Help page to learn more about our services.

If you are a student survivor of sexual assault, click here to learn how Sanctuary can help.

For support on a national level, you can contact the National Sexual Assault Hotline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673) or the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-SAFE (7233).

Let’s stand together, rock our denim, and create a world free from sexual violence and domestic abuse. We believe in a brighter future for all and won’t stop fighting until we get there.